Discussion - Member to Member Sales - Research Center

Discussion - Member to Member Sales - Research Center

Anyone help me translate this please?

Thanks.

Peter

Login to Like

this post

The 3rd & 4th characters (from the left) means "prisoner".

However, in the context of the entire phrase, it should be "Hong Kong Internment Camp".

It's more likely early half of 1940s.

Login to Like

this post

HongKong War Captive Camp

Login to Like

this post

Thank you both; that explains a lot! This was amongst my uncle's papers and he was imprisoned by the Japanese in the Allied POW camp in Shamshipo, Hong Kong. Not sure what the stamps are doing on the paper though.

Cheers,

Peter

1 Member

likes this post.

Login to Like.

"Not sure what the stamps are doing on the paper though."

If it bothers you, remove them and send them to me. I'll make sure the stamps don't bother you again.

Login to Like

this post

This thread helped me out, too. In my collection are two Hong Kong POW covers, purchased at separate auctions. One was sent to a prisoner, Pte. R. Dalzell, from his wife in Winnipeg, the other from Dalzell to his wife from Hong Kong. The one from Dalzell includes a red handstamp with the two characters that mean "prisoner;" I didn't have that information before I read it here.

Here is the cover posted by the prisoner; the Canadian stamp was added when the letter arrived in Ottawa. I'm not sure of how mail was transported from Japan to Canada.

Here's a detail image of the handstamp, the first two characters of which mean "prisoner," according to KHJ:

KHJ, can you please tell me the meaning of the other two characters?

Dalzell was taken prisoner along with many other Canadians when his unit, the Winnipeg Grenadiers, was overwhelmed by the Japanese on December 7, 1941, the same day as the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

My understanding is that Pte. Dalzell survived his incarceration, returned to Canada, and eventually became the head of the Canadian Hong Kong POW's association, but that may not be accurate. More research ahead!

Bob

Login to Like

this post

"can you please tell me the meaning of the other two characters?"

Counting from the top, the 3rd character is the standard Chinese character for "post/postal". You will sometimes see this (or the simplified character) on Chinese stamps and on the post office signs. Combined with the 4th character, the pair means "posted".

So the handstamp literally means prisoner post, but not in the sense of an actual post office or postal service, but in the sense of "posted by a prisoner". The censor label has been partially torn away, so it is not clear who examined it.

The lack of any other markings on it suggests that it was examined by a censor and taken by somebody to Canada in 1944, where it was posted through the regular mail system there. But that is just guesswork on my part. Not clear what role Hasegawa played in this.

Login to Like

this post

I was reading a article regarding HongKong international mail (including those from China) during Japanese occupation from 1941 to 1945. It said during that period, mails were detained by Japanese, there were only delivered after its surrender.

The prisoner cover Bob has may not posted by regular postal system, it was delivered by internal Japanese system, so it went through Japan.

Here are two covers I downloaded (1941' mail delivered in 1945)

Login to Like

this post

Nice covers, Sam.

It is true that mail was held by the Japanese and not discovered/delivered until well after the fact by the Allies. The Japanese soldiers viewed prisoners of war with disdain and put very little effort toward meeting their personal needs.

On the other hand, there is no evidence of any Asian postage or postmarks on Bob's cover, which is why I suggested that it was taken through other channels to Canada and then delivered through the Canadian postal system. Somebody put Canadian postage on Bob's cover, and it is unlikely that this was done in Asia. Also, note that it was delivered in 1944, not post-war. The censor label is one of the keys; unfortunately, it is not complete.

Login to Like

this post

Bob, this might interest you. Here is the entry for this serviceman, in the Hong Kong War Diary web site

Dalzell, Robert Private H/6268 (XD4)

Being Canadian, he was most likely at the Shamshiupo Camp on Kowloon side, or possibly the North Point Camp on Hong Kong Island. If the former, he was with my great uncle, uncle, and godfather.

Peter

Login to Like

this post

I've only had a chance to read through this thread quickly, so apologies in advance if I missed something or it's already been answered.

In the 4-character vertical image that Bob posted, the last 2 characters in Japanese always (or nearly always) go together as "post" or "postal" or somehow related to postal matters.

They're read "yuubin", and often are the _first_ 2 characters in "postal" vocabulary. For example, "post office" is "yuubin kyoku", and "postage stamp" is "yuubin kitte".

So I think they're being used to describe some kind of "post" or "mail", as in "soldier's mail" or something like that. (It's not "military mail", because I would recognize that right off.)

I'll try in a few minutes to check a Japanese language philatelic resource and see if I can determine what those first 2 characters are, in this context.

Login to Like

this post

Oh, I just read through Bob's post again, and realize he said that the first characters mean "prisoner", in which case the 4 characters together mean "prisoner(s) mail" or "prisoner(s) post".

Sorry to be in a rush and not as deliberative as I'd like to be about matters like this.

Login to Like

this post

Ok, I just had a chance to check in both a regular Japanese language reference and in a specialized Japanese philatelic reference, and this:

means "prisoner of war mail".

The reading of those characters would be: "fu-ryo yuubin". (The pronunciation of "ryo" is closer to "dyo" than our regular "r" sound.)

The philatelic source also cited the French term, "service des prisonniers de guerre", which corresponds to the printing at the front top of that card.

Hope this is helpful.

Login to Like

this post

Just one small nuance about those first two characters: in Japanese, at least (and perhaps in Chinese, KHJ?) it has the meaning of "captive".

Login to Like

this post

Yes, it can mean prisoner or captive, so that means prisoner in the sense of prisoner-of-war. I wasn't sure of the context of the original post, so I translated it as Internment Camp.

In Bob's example, the mail is clearly from a POW. The only question is, how it got to Canada to enter the Canadian mailstream.

Login to Like

this post

Khj, when I first wrote my replies, I didn't realize he had also shown the full card further up-thread, so I didn't have the context when I composed those replies. So I wanted to make sure, to prove to me, that this was POW, or detainee, as opposed to a prisoner as someone who has committed a crime and/or run afoul of the criminal justice system.

As for how the mail got to Canada, I'm sure it's been written about somewhere and I wonder if a Google search might reveal it. My offhand and uninformed guess is that Switzerland might be involved, but that's just pure speculation.

If I get time, I'll try to look online, but hope that someone who may know this area might weigh in more authoritatively in the meantime!

Login to Like

this post

This seemed to be the best result from 5 minutes of Googling:

https://www.forces-war-records.co.uk/prisoners-of-war-of-the-japanese-1939-1945

Its scope is Allied POWs (including Canada and US), not just UK POWs.

If you put "mail" in the search term for the page, which is quite long, you'll see some pertinent sections.

From a brief skimming, it looks like the Soviet Union may have provided some mail transport in the earlier part of the war. It also says that the Japanese were not particularly good about making sure POW got out, but did say that they were better about ICRC visits, and would pass mail along at that time. (I'm summarizing way too roughly here.)

Login to Like

this post

I think I posted this before, but here it is again. This is Red Cross mail sent to my godfather in the Shamshipo Camp in Hong Kong. The red Chinese (Japanese?) characters on the left are the same as the others posted; I didn't notice this before!

Login to Like

this post

Peter, I must've missed that the last time, so I'm glad you decided to show it again.

What a cover! Just on its philatelic merits alone, it's quite something, and then for there to be such a personal connection -- wow!

Thank you for sharing it!

Login to Like

this post

Dave and Kim, I was reading this post through again and something occurred to me; sorry if this sounds incredibly stupid.

Are Japanese and Chinese script the same? I thought Japanese, like Korean, used its own script? I believe it is called Kanji, if I'm not mistaken. The examples I (and Bob) posted here seem to show Chinese script but were translated as Japanese words. Am I missing something?

Domo arigato, Mr. Robato!

Login to Like

this post

Hi, Peter --

This is not a stupid question -- it's actually a really good one!

With Japanese, there are actually 3 different writing systems, and all of them are used together.

Kanji are the ideographic characters that came from (or heavily influenced by? -- I think "came from".) Chinese. (I know you know this, but ... ) Ideographic means that how the characters are pronounced has nothing to do with how they're written. For us, numerals are maybe the best example of this.

Unless I'm mistaken, Chinese only uses kanji (except that I don't know what they're called in Chinese!).

But there are also 2 phonetic alphabets that Japanese uses.

The main one is called hiragana, and that really provides the "completion" to sentences. It's how verbs are conjugated, prepositions are used, etc. It's a nice-looking, almost cursive phonetic system. There are 47 46 of them, and they have a specific pronunciation, so it's not hard to learn and use them. (It's the kanji that are the killer!)

The 3rd phonetic alphabet is called katakana, and it functions the same way hiragana does, except that it's used for foreign words that come into the language, like (I'll use the romanization) "konpyuutaa" (computer), "napukin" (napkin), and on and on. (By now, most loan-words come from English, but there are some that have been around a long time, like "pan", which means "bread", and came from the Portuguese! (Thought you'd like that!)) These characters have sharp angles to them, and does not have, to me, the aesthetic pleasure that hiragana has.

So, in regular, non-simplified written Japanese, a sentence could very easily have all 3 writing systems in it. Kanji would likely carry most of the load, with hiragana mostly rounding things out. But if there is a foreign word in the sentence, then it'll be written in katakana.

(Note: I can think of exceptions to everything I just said above, so I want to go on record saying that these are generalizations.)

Does this help a little bit?

-- Dave

1 Member

likes this post.

Login to Like.

And here's a nice little article, written by a translation company in Tokyo, that explains in a bit of detail of how kanji and Chinese characters are related to each other.

(And "kanji" means Chinese characters, so that sentence above kind of folds back up on itself -- lol!)

http://www.arc-japanese-translation.com/chinese/04tidbits.html

Login to Like

this post

Thanks Dave; I did learn a lot from this!

Dave Philatarium said:

"like "pan", which means "bread", and came from the Portuguese! (Thought you'd like that!)"

Yes, thanks from the other Mediterranean ancestors in my family.

Here's a language tidbit: There are a couple "false friends" in Macanese (patois spoken by the Portuguese from Macau) that sound the same Japanese words, but mean something very different.

Miso in Japanese is a seasoning produced from fermented soybeans; in Macanese, it means "piss"! (the Portuguese word is "mijo")

Sakana in Japanese means food eaten in accompaniment with alcohol; in Macanese, it means something equivalent to calling someone an ***hole!

I wonder who influenced whom when the two cultures came together in the five hundred years ago?

Peter

Login to Like

this post

First, a correction to my earlier post.

There are 46 hiragana, not 47.

There are, however, 47 Japanese prefectures.

Another example of my rapid slide into Oldtimers' Disease.

Login to Like

this post

Peter -- that's very interesting! All these treacherous minefields in language ...

(With enough time, I'll manage to step onto them all!)

And then, of course, I couldn't help but notice the similarity between "mijo" in Portugese and "mijo" in Spanish ("son" and term of affection). I'm assuming the "j" is pronounced in Portuguese?

Login to Like

this post

Yes, the j is pronounced and not like h in Spanish; more like a slurred "mee-choo". A family member who speaks Spanish said Portuguese to her was like speaking Castilian Spanish with marbles in your mouth. I've heard less flattering examples!

Dave, there must be regional dialects in Japan too, as there are in China? I recall living in Honolulu and hearing those descended from Honshu looking down at how the Okinawans spoke, for example.

Login to Like

this post

I just happened to be back on line, Peter -- I'm typically not this quick with a response!

There are both regional dialects and accents in Japan, plus some distinctions made about race (or perhaps "Japanese-ness" would be a better term). I know one can travel even just a hundred miles or so from Tokyo and start running into at least the accent differences.

Tokyo and Osaka are about 300 miles apart, and there are regional differences in some expressions, greetings, some vocabulary, and, of course, in cuisine. (Kansai area vs. Kanto area)

Here are a couple of recent articles:

http://www.cnn.com/2015/04/28/travel/discover-japan-kansai-vs-kanto/

http://www.tofugu.com/2014/02/19/kansai-vs-kanto-why-cant-we-all-just-get-along/

Then there are those racial/Japanese-ness issues. But, in a overly broad general sense, one could say that, at least historically, the people in the middle of Japan have tended to look down on those at the tips of Japan, going both north to Hokkaido and down south to Okinawa (which, to keep it in philatelic terms, were the Ryukyu Islands).

(I cringe as I write that last paragraph, because that's way too general, and I don't want to get into specifics, in the same way that I wouldn't want to do that in talking about people in the US and perceptions about region and group.)

But these are really good questions, and have caused me to think. (You wouldn't have been a professor at some time in your past, would you have?  )

)

If or when I ever get my blog up and running on Japanese philately and the intersection of stamps and culture, I'd love for you to participate there -- you're teasing out all these great topics to explore!

1 Member

likes this post.

Login to Like.

A Chinese cover in my collection and now on my web site — The MiG 15 fighter re-defined aerial combat — resulted in more than a little confusion for me, and differences of opinion among Chinese speakers who have attempted to translate the address and return address.

This is the cover (the back is blank):

The web page discusses the various translations that were provided to me. I would appreciate it any Chinese speaking members of Stamporama could confirm the correctness of any of those translations, or offer one that they believe to be accurate.

Bob

Login to Like

this post

I only took a quick look.

The transcription of the proper names will depend on whether you are transcribing from Mandarin or Cantonese (the written language of the various dialects is basically the same, in that time frame, traditional script; but the words are pronounced differently in the various dialects).

One of the names in question, will be Mr. Kin Sze (or See) Wong from Cantonese, and Mr. Jiansi Huang (using current Mainland China transcription for Mandarin). If we used the Mandarin transcription used at that time, it would be Mr. Chien-Si Huang.

Given the sender/receiver address, it would be more proper to describe the letter in Cantonese transcription for historical accuracy -- hence, Mr. Kin Sze Wong (in Chinese, of course, it is actually Wong Kin Sze Mister. I am not a Cantonese speaker, so I am going with Sze instead of See, but I can see where both might be used.

The transcription "Jian En Wang" is definitely incorrect. I can understand this error. In Mandarin, Huang 黄 and Wang 王 are pronounced fairly similarly although written very differently. Some Mandarin speaking areas (or dual dialect speakers) may "mispronounce" one or both, causing confusion when transcribing to English. Secondly, the word being incorrectly transcribed as "En" æ© actually looks VERY VERY similar to word "Si/Sze/See" æ€ that is on the letter.

Sorry, I didn't read your entire blog. If you have any more specific questions, feel free to ask.

Login to Like

this post

Thank you, KHJ. I will attempt to incorporate your translation(s) into my web page.

The thought strikes me that the main difficulty I've had in writing about this cover is because of my perception that I must provide a translation in English of the Chinese characters, characters which can be translated in differing but still accurate ways. And it seems to me, after considering the question further, that the Chinese characters, which were never intended to be translated into English or any other language, can be understood perfectly by anyone who reads Chinese. Are these correct assumptions?

Bob

Login to Like

this post

Yes. In the context of the letter, the native Chinese reader can fairly easily recognize what is simply a proper name and when the meaning of the word is to be applied.

For an English example, when we see "Robert" we immediately think of the name and don't try to work "bright fame" into the meaning of the sentence. Robert is Robert, even though it might have meant "bright fame" (in the origin German).

Ironically, in translations from English into Chinese, the Chinese run into a parallel problem -- when is it a name, and when is it simply transcription INTO Chinese? Therefore, on some books/documents in which the reader may be unfamiliar with the material, proper names transcribed into Chinese will sometimes have a solid line drawn next to it, to indicate that the Chinese characters are a transcription from English and not a translation (otherwise, the sentence would make no sense in Chinese!).

Obviously, I am not a professional translator. But I often help with casual (non-formal) translation. In general (for Chinese written language) proper names of people and geographical locations are transcribed based on sound. Proper names of organizations, businesses, events... are often a mix of transcription/translation because there is usually a descriptor in the name that describes what kind of organization/business/event...

So for your letter, you will find that point of controversy is largely with transcription problems, not translation problems (as I and others noted, one of the offered transcriptions for Mr. Wong was incorrectly transcribed as Mr. Wang).

In transcribing proper names, there are a lot of problems. The proper solution will depend on your target audience. If from a historical perspective, you will transcribe based on the transcription standard of that time. Therefore, older documents you would transcribe as Peking, newer documents you would transcribe as Beijing. If your target is simply the modern reader, then you will transcribe as Beijing. Then there would also be the issue of name changes (Western equivalent examples would be Byzantium/Constantinople/Istanbul, St.Petersburg/Petrograd/Leningrad/St.Petersburg...)

The additional complication for transcribing Chinese in historical context is dialect spoken. In your letter, based on sender/recipient, it is likely Cantonese. Therefore, historical the proper names should probably be transcribed based on the Cantonese pronunciation. If it is for the modern reader, then transcribe as Hanyu Pinyin as that is the current most widely used standard.

You will need to make a choice in this matter.

1 Member

likes this post.

Login to Like.

I took another quick look at your article. It's very well written and very interesting!

Also another very quick look at the postmark translation. A couple of points:

"At the bottom of the address is the notation "NG PING," probably the name of a local post office. The date of postmark date is unclear; it may be November 11."

The cancel date (top character is circled in red), I believe is 21, not 11. The bottom character is definitely 1. The top character is definitely NOT 10 (å). It can only be the character for 0 (零), beginning (åˆ) or 20 (廿). The top character might look like a badly smudged 零. Not a collector of postmarks, but I don't recall ever seeing a 0 (零) nor beginning (åˆ) as a date leader on cancels of that area/time, so I will rule both out. Normally, 20 is written as (二å, would be vertically written in the postmark). But for calendars, the traditional character used is actually (廿). I believe the top character in the date is actually a very badly smudged/damaged 廿. Hence, I suggest the postmark date is more likely 21Nov1954.

Regarding the "Ng Ping" being at the bottom of the address, I think you misunderstood? It is the 2 characters at the bottom of the postmark (see purple circle) -- that is a transcription based on Cantonese pronunciation. I believe that transcription and its interpretation may be in error. The postmark top and bottom arc segments will always be read in the same direction, although that direction may vary among the different postmark areas and time periods. In your example, the top Guangzhou (also historically transcribed as Canton or Kwangchow) is clearly read from left to right, therefore the bottom arc segment is also read from left to right. Therefore, it would be "Ping Ng", not "Ng Ping".

However, in my opinion, it is still not "Ping Ng". The original incorrect transcription "Ng Ping" might actually make sense as a post office or district name, because it would mean "five peaces", which is actually a pretty name. But I don't think that's what it says. Your friend thought they saw the characters "平五", which makes no sense when read from left to right. I think it says "下五", where the left character is badly smudged. 下 means down (or after, next...), and in the context of time stamp we can assume it is shorthand for ä¸‹åˆ (afternoon). Therefore, the bottom 2 characters (to me) mean 5PM.

Sorry for the long post. Just trying to explain why I think there was an error, and also explain my reasoning.

I'll try to look over the rest of the translation later this week.

Again, very nice article!

k

Login to Like

this post

Again, thank you! I told my wife that, based on your first post, I had had an epiphany, and it seems I was right. I'll re-work the pertinent portion of the web page.

Bob

Login to Like

this post

While the name of the road is normally transcribed, I think you did a good job of explaining the meaning of the name of the road. Things like that are very useful, informative, and make for good reading.

Since I am neither a native reader/speaker of Mandarin/Cantonese Chinese, I welcome any comments or corrections to my transcriptions/translations/explanations.

Login to Like

this post

I can pass along two reliable Chinese/Japanese factoids:

- While Chinese characters appear in Japanese, they often have an unrelated meaning. This is usually taken to mean that the graphicon itself was 'borrowed', eg, found attractive or useful for one reason or another.

- If you are dealing with Chinese military mail - in the broadest sense of that word - it can be useful to remember that the Chinese navy works in Cantonese, while the rest of the Chinese military works in Mandarin. Yes, they use translators at the different command levels & points-of-contact to facilitate inter-service cooperation.

Cheers,

Login to Like

this post

Bob and I are talking about unrelated issues under the same topic heading and general intention: Chinese translation. As my question was answered earlier, I have no problem with the discussion continuing in another direction and, in fact, have learned a lot more as the nuances of Chinese and Japanese writing are explained.

I did know that spoken Chinese (and now I know, spoken Japanese) had a lot of variety depending on regions, and even within regions. Where I grew up through my early teens, Hong Kong, we were exposed to mainly Cantonese and its dialects (not sure if that is the correct term for the variations on "typical" Cantonese). Farmers in the New Territories near the border with China, for example, spoke a type of Cantonese that we city dwellers could almost not understand, and those who were from areas closer to Canton itself spoke differently that those who grew up in Hong Kong proper. However, all Chinese who could read, would be able to read the script independent of how they spoke the language. I guess this is like written English, which can be read by Canadians, US Americans, English, Irish, Scots, Australians, etc. despite differences in spoken English between and within these groups.

Login to Like

this post

07:39:57am

" ... it can be useful to remember that the Chinese navy works in Cantonese, while the rest of the Chinese military works in Mandarin. Yes, they use translators at the different command levels & points-of-contact to facilitate inter-service cooperation. ..."

Amazing detail. Does the CIA know this ?

What a potential source of confusion.

1 Member

likes this post.

Login to Like.

11:05:57am

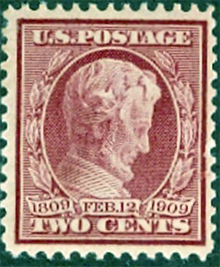

This is stamped on paper with postal and revenue stamps attached on the plain reverse. No other patterns; only a partial so no addressee or other indications. Stamps are China, circa 1930s to 1940s.

Anyone help me translate this please?

Thanks.

Peter

Login to Like

this post

re: Chinese translation please

The 3rd & 4th characters (from the left) means "prisoner".

However, in the context of the entire phrase, it should be "Hong Kong Internment Camp".

It's more likely early half of 1940s.

Login to Like

this post

11:57:32am

re: Chinese translation please

HongKong War Captive Camp

Login to Like

this post

03:29:57pm

re: Chinese translation please

Thank you both; that explains a lot! This was amongst my uncle's papers and he was imprisoned by the Japanese in the Allied POW camp in Shamshipo, Hong Kong. Not sure what the stamps are doing on the paper though.

Cheers,

Peter

1 Member

likes this post.

Login to Like.

re: Chinese translation please

"Not sure what the stamps are doing on the paper though."

If it bothers you, remove them and send them to me. I'll make sure the stamps don't bother you again.

Login to Like

this post

re: Chinese translation please

This thread helped me out, too. In my collection are two Hong Kong POW covers, purchased at separate auctions. One was sent to a prisoner, Pte. R. Dalzell, from his wife in Winnipeg, the other from Dalzell to his wife from Hong Kong. The one from Dalzell includes a red handstamp with the two characters that mean "prisoner;" I didn't have that information before I read it here.

Here is the cover posted by the prisoner; the Canadian stamp was added when the letter arrived in Ottawa. I'm not sure of how mail was transported from Japan to Canada.

Here's a detail image of the handstamp, the first two characters of which mean "prisoner," according to KHJ:

KHJ, can you please tell me the meaning of the other two characters?

Dalzell was taken prisoner along with many other Canadians when his unit, the Winnipeg Grenadiers, was overwhelmed by the Japanese on December 7, 1941, the same day as the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

My understanding is that Pte. Dalzell survived his incarceration, returned to Canada, and eventually became the head of the Canadian Hong Kong POW's association, but that may not be accurate. More research ahead!

Bob

Login to Like

this post

re: Chinese translation please

"can you please tell me the meaning of the other two characters?"

Counting from the top, the 3rd character is the standard Chinese character for "post/postal". You will sometimes see this (or the simplified character) on Chinese stamps and on the post office signs. Combined with the 4th character, the pair means "posted".

So the handstamp literally means prisoner post, but not in the sense of an actual post office or postal service, but in the sense of "posted by a prisoner". The censor label has been partially torn away, so it is not clear who examined it.

The lack of any other markings on it suggests that it was examined by a censor and taken by somebody to Canada in 1944, where it was posted through the regular mail system there. But that is just guesswork on my part. Not clear what role Hasegawa played in this.

Login to Like

this post

07:44:41pm

re: Chinese translation please

I was reading a article regarding HongKong international mail (including those from China) during Japanese occupation from 1941 to 1945. It said during that period, mails were detained by Japanese, there were only delivered after its surrender.

The prisoner cover Bob has may not posted by regular postal system, it was delivered by internal Japanese system, so it went through Japan.

Here are two covers I downloaded (1941' mail delivered in 1945)

Login to Like

this post

re: Chinese translation please

Nice covers, Sam.

It is true that mail was held by the Japanese and not discovered/delivered until well after the fact by the Allies. The Japanese soldiers viewed prisoners of war with disdain and put very little effort toward meeting their personal needs.

On the other hand, there is no evidence of any Asian postage or postmarks on Bob's cover, which is why I suggested that it was taken through other channels to Canada and then delivered through the Canadian postal system. Somebody put Canadian postage on Bob's cover, and it is unlikely that this was done in Asia. Also, note that it was delivered in 1944, not post-war. The censor label is one of the keys; unfortunately, it is not complete.

Login to Like

this post

09:34:59pm

re: Chinese translation please

Bob, this might interest you. Here is the entry for this serviceman, in the Hong Kong War Diary web site

Dalzell, Robert Private H/6268 (XD4)

Being Canadian, he was most likely at the Shamshiupo Camp on Kowloon side, or possibly the North Point Camp on Hong Kong Island. If the former, he was with my great uncle, uncle, and godfather.

Peter

Login to Like

this post

re: Chinese translation please

I've only had a chance to read through this thread quickly, so apologies in advance if I missed something or it's already been answered.

In the 4-character vertical image that Bob posted, the last 2 characters in Japanese always (or nearly always) go together as "post" or "postal" or somehow related to postal matters.

They're read "yuubin", and often are the _first_ 2 characters in "postal" vocabulary. For example, "post office" is "yuubin kyoku", and "postage stamp" is "yuubin kitte".

So I think they're being used to describe some kind of "post" or "mail", as in "soldier's mail" or something like that. (It's not "military mail", because I would recognize that right off.)

I'll try in a few minutes to check a Japanese language philatelic resource and see if I can determine what those first 2 characters are, in this context.

Login to Like

this post

re: Chinese translation please

Oh, I just read through Bob's post again, and realize he said that the first characters mean "prisoner", in which case the 4 characters together mean "prisoner(s) mail" or "prisoner(s) post".

Sorry to be in a rush and not as deliberative as I'd like to be about matters like this.

Login to Like

this post

re: Chinese translation please

Ok, I just had a chance to check in both a regular Japanese language reference and in a specialized Japanese philatelic reference, and this:

means "prisoner of war mail".

The reading of those characters would be: "fu-ryo yuubin". (The pronunciation of "ryo" is closer to "dyo" than our regular "r" sound.)

The philatelic source also cited the French term, "service des prisonniers de guerre", which corresponds to the printing at the front top of that card.

Hope this is helpful.

Login to Like

this post

re: Chinese translation please

Just one small nuance about those first two characters: in Japanese, at least (and perhaps in Chinese, KHJ?) it has the meaning of "captive".

Login to Like

this post

re: Chinese translation please

Yes, it can mean prisoner or captive, so that means prisoner in the sense of prisoner-of-war. I wasn't sure of the context of the original post, so I translated it as Internment Camp.

In Bob's example, the mail is clearly from a POW. The only question is, how it got to Canada to enter the Canadian mailstream.

Login to Like

this post

re: Chinese translation please

Khj, when I first wrote my replies, I didn't realize he had also shown the full card further up-thread, so I didn't have the context when I composed those replies. So I wanted to make sure, to prove to me, that this was POW, or detainee, as opposed to a prisoner as someone who has committed a crime and/or run afoul of the criminal justice system.

As for how the mail got to Canada, I'm sure it's been written about somewhere and I wonder if a Google search might reveal it. My offhand and uninformed guess is that Switzerland might be involved, but that's just pure speculation.

If I get time, I'll try to look online, but hope that someone who may know this area might weigh in more authoritatively in the meantime!

Login to Like

this post

re: Chinese translation please

This seemed to be the best result from 5 minutes of Googling:

https://www.forces-war-records.co.uk/prisoners-of-war-of-the-japanese-1939-1945

Its scope is Allied POWs (including Canada and US), not just UK POWs.

If you put "mail" in the search term for the page, which is quite long, you'll see some pertinent sections.

From a brief skimming, it looks like the Soviet Union may have provided some mail transport in the earlier part of the war. It also says that the Japanese were not particularly good about making sure POW got out, but did say that they were better about ICRC visits, and would pass mail along at that time. (I'm summarizing way too roughly here.)

Login to Like

this post

04:04:07pm

re: Chinese translation please

I think I posted this before, but here it is again. This is Red Cross mail sent to my godfather in the Shamshipo Camp in Hong Kong. The red Chinese (Japanese?) characters on the left are the same as the others posted; I didn't notice this before!

Login to Like

this post

re: Chinese translation please

Peter, I must've missed that the last time, so I'm glad you decided to show it again.

What a cover! Just on its philatelic merits alone, it's quite something, and then for there to be such a personal connection -- wow!

Thank you for sharing it!

Login to Like

this post

11:34:49am

re: Chinese translation please

Dave and Kim, I was reading this post through again and something occurred to me; sorry if this sounds incredibly stupid.

Are Japanese and Chinese script the same? I thought Japanese, like Korean, used its own script? I believe it is called Kanji, if I'm not mistaken. The examples I (and Bob) posted here seem to show Chinese script but were translated as Japanese words. Am I missing something?

Domo arigato, Mr. Robato!

Login to Like

this post

re: Chinese translation please

Hi, Peter --

This is not a stupid question -- it's actually a really good one!

With Japanese, there are actually 3 different writing systems, and all of them are used together.

Kanji are the ideographic characters that came from (or heavily influenced by? -- I think "came from".) Chinese. (I know you know this, but ... ) Ideographic means that how the characters are pronounced has nothing to do with how they're written. For us, numerals are maybe the best example of this.

Unless I'm mistaken, Chinese only uses kanji (except that I don't know what they're called in Chinese!).

But there are also 2 phonetic alphabets that Japanese uses.

The main one is called hiragana, and that really provides the "completion" to sentences. It's how verbs are conjugated, prepositions are used, etc. It's a nice-looking, almost cursive phonetic system. There are 47 46 of them, and they have a specific pronunciation, so it's not hard to learn and use them. (It's the kanji that are the killer!)

The 3rd phonetic alphabet is called katakana, and it functions the same way hiragana does, except that it's used for foreign words that come into the language, like (I'll use the romanization) "konpyuutaa" (computer), "napukin" (napkin), and on and on. (By now, most loan-words come from English, but there are some that have been around a long time, like "pan", which means "bread", and came from the Portuguese! (Thought you'd like that!)) These characters have sharp angles to them, and does not have, to me, the aesthetic pleasure that hiragana has.

So, in regular, non-simplified written Japanese, a sentence could very easily have all 3 writing systems in it. Kanji would likely carry most of the load, with hiragana mostly rounding things out. But if there is a foreign word in the sentence, then it'll be written in katakana.

(Note: I can think of exceptions to everything I just said above, so I want to go on record saying that these are generalizations.)

Does this help a little bit?

-- Dave

1 Member

likes this post.

Login to Like.

re: Chinese translation please

And here's a nice little article, written by a translation company in Tokyo, that explains in a bit of detail of how kanji and Chinese characters are related to each other.

(And "kanji" means Chinese characters, so that sentence above kind of folds back up on itself -- lol!)

http://www.arc-japanese-translation.com/chinese/04tidbits.html

Login to Like

this post

01:46:20pm

re: Chinese translation please

Thanks Dave; I did learn a lot from this!

Dave Philatarium said:

"like "pan", which means "bread", and came from the Portuguese! (Thought you'd like that!)"

Yes, thanks from the other Mediterranean ancestors in my family.

Here's a language tidbit: There are a couple "false friends" in Macanese (patois spoken by the Portuguese from Macau) that sound the same Japanese words, but mean something very different.

Miso in Japanese is a seasoning produced from fermented soybeans; in Macanese, it means "piss"! (the Portuguese word is "mijo")

Sakana in Japanese means food eaten in accompaniment with alcohol; in Macanese, it means something equivalent to calling someone an ***hole!

I wonder who influenced whom when the two cultures came together in the five hundred years ago?

Peter

Login to Like

this post

re: Chinese translation please

First, a correction to my earlier post.

There are 46 hiragana, not 47.

There are, however, 47 Japanese prefectures.

Another example of my rapid slide into Oldtimers' Disease.

Login to Like

this post

re: Chinese translation please

Peter -- that's very interesting! All these treacherous minefields in language ...

(With enough time, I'll manage to step onto them all!)

And then, of course, I couldn't help but notice the similarity between "mijo" in Portugese and "mijo" in Spanish ("son" and term of affection). I'm assuming the "j" is pronounced in Portuguese?

Login to Like

this post

04:11:28pm

re: Chinese translation please

Yes, the j is pronounced and not like h in Spanish; more like a slurred "mee-choo". A family member who speaks Spanish said Portuguese to her was like speaking Castilian Spanish with marbles in your mouth. I've heard less flattering examples!

Dave, there must be regional dialects in Japan too, as there are in China? I recall living in Honolulu and hearing those descended from Honshu looking down at how the Okinawans spoke, for example.

Login to Like

this post

re: Chinese translation please

I just happened to be back on line, Peter -- I'm typically not this quick with a response!

There are both regional dialects and accents in Japan, plus some distinctions made about race (or perhaps "Japanese-ness" would be a better term). I know one can travel even just a hundred miles or so from Tokyo and start running into at least the accent differences.

Tokyo and Osaka are about 300 miles apart, and there are regional differences in some expressions, greetings, some vocabulary, and, of course, in cuisine. (Kansai area vs. Kanto area)

Here are a couple of recent articles:

http://www.cnn.com/2015/04/28/travel/discover-japan-kansai-vs-kanto/

http://www.tofugu.com/2014/02/19/kansai-vs-kanto-why-cant-we-all-just-get-along/

Then there are those racial/Japanese-ness issues. But, in a overly broad general sense, one could say that, at least historically, the people in the middle of Japan have tended to look down on those at the tips of Japan, going both north to Hokkaido and down south to Okinawa (which, to keep it in philatelic terms, were the Ryukyu Islands).

(I cringe as I write that last paragraph, because that's way too general, and I don't want to get into specifics, in the same way that I wouldn't want to do that in talking about people in the US and perceptions about region and group.)

But these are really good questions, and have caused me to think. (You wouldn't have been a professor at some time in your past, would you have?  )

)

If or when I ever get my blog up and running on Japanese philately and the intersection of stamps and culture, I'd love for you to participate there -- you're teasing out all these great topics to explore!

1 Member

likes this post.

Login to Like.

re: Chinese translation please

A Chinese cover in my collection and now on my web site — The MiG 15 fighter re-defined aerial combat — resulted in more than a little confusion for me, and differences of opinion among Chinese speakers who have attempted to translate the address and return address.

This is the cover (the back is blank):

The web page discusses the various translations that were provided to me. I would appreciate it any Chinese speaking members of Stamporama could confirm the correctness of any of those translations, or offer one that they believe to be accurate.

Bob

Login to Like

this post

re: Chinese translation please

I only took a quick look.

The transcription of the proper names will depend on whether you are transcribing from Mandarin or Cantonese (the written language of the various dialects is basically the same, in that time frame, traditional script; but the words are pronounced differently in the various dialects).

One of the names in question, will be Mr. Kin Sze (or See) Wong from Cantonese, and Mr. Jiansi Huang (using current Mainland China transcription for Mandarin). If we used the Mandarin transcription used at that time, it would be Mr. Chien-Si Huang.

Given the sender/receiver address, it would be more proper to describe the letter in Cantonese transcription for historical accuracy -- hence, Mr. Kin Sze Wong (in Chinese, of course, it is actually Wong Kin Sze Mister. I am not a Cantonese speaker, so I am going with Sze instead of See, but I can see where both might be used.

The transcription "Jian En Wang" is definitely incorrect. I can understand this error. In Mandarin, Huang 黄 and Wang 王 are pronounced fairly similarly although written very differently. Some Mandarin speaking areas (or dual dialect speakers) may "mispronounce" one or both, causing confusion when transcribing to English. Secondly, the word being incorrectly transcribed as "En" æ© actually looks VERY VERY similar to word "Si/Sze/See" æ€ that is on the letter.

Sorry, I didn't read your entire blog. If you have any more specific questions, feel free to ask.

Login to Like

this post

re: Chinese translation please

Thank you, KHJ. I will attempt to incorporate your translation(s) into my web page.

The thought strikes me that the main difficulty I've had in writing about this cover is because of my perception that I must provide a translation in English of the Chinese characters, characters which can be translated in differing but still accurate ways. And it seems to me, after considering the question further, that the Chinese characters, which were never intended to be translated into English or any other language, can be understood perfectly by anyone who reads Chinese. Are these correct assumptions?

Bob

Login to Like

this post

re: Chinese translation please

Yes. In the context of the letter, the native Chinese reader can fairly easily recognize what is simply a proper name and when the meaning of the word is to be applied.

For an English example, when we see "Robert" we immediately think of the name and don't try to work "bright fame" into the meaning of the sentence. Robert is Robert, even though it might have meant "bright fame" (in the origin German).

Ironically, in translations from English into Chinese, the Chinese run into a parallel problem -- when is it a name, and when is it simply transcription INTO Chinese? Therefore, on some books/documents in which the reader may be unfamiliar with the material, proper names transcribed into Chinese will sometimes have a solid line drawn next to it, to indicate that the Chinese characters are a transcription from English and not a translation (otherwise, the sentence would make no sense in Chinese!).

Obviously, I am not a professional translator. But I often help with casual (non-formal) translation. In general (for Chinese written language) proper names of people and geographical locations are transcribed based on sound. Proper names of organizations, businesses, events... are often a mix of transcription/translation because there is usually a descriptor in the name that describes what kind of organization/business/event...

So for your letter, you will find that point of controversy is largely with transcription problems, not translation problems (as I and others noted, one of the offered transcriptions for Mr. Wong was incorrectly transcribed as Mr. Wang).

In transcribing proper names, there are a lot of problems. The proper solution will depend on your target audience. If from a historical perspective, you will transcribe based on the transcription standard of that time. Therefore, older documents you would transcribe as Peking, newer documents you would transcribe as Beijing. If your target is simply the modern reader, then you will transcribe as Beijing. Then there would also be the issue of name changes (Western equivalent examples would be Byzantium/Constantinople/Istanbul, St.Petersburg/Petrograd/Leningrad/St.Petersburg...)

The additional complication for transcribing Chinese in historical context is dialect spoken. In your letter, based on sender/recipient, it is likely Cantonese. Therefore, historical the proper names should probably be transcribed based on the Cantonese pronunciation. If it is for the modern reader, then transcribe as Hanyu Pinyin as that is the current most widely used standard.

You will need to make a choice in this matter.

1 Member

likes this post.

Login to Like.

re: Chinese translation please

I took another quick look at your article. It's very well written and very interesting!

Also another very quick look at the postmark translation. A couple of points:

"At the bottom of the address is the notation "NG PING," probably the name of a local post office. The date of postmark date is unclear; it may be November 11."

The cancel date (top character is circled in red), I believe is 21, not 11. The bottom character is definitely 1. The top character is definitely NOT 10 (å). It can only be the character for 0 (零), beginning (åˆ) or 20 (廿). The top character might look like a badly smudged 零. Not a collector of postmarks, but I don't recall ever seeing a 0 (零) nor beginning (åˆ) as a date leader on cancels of that area/time, so I will rule both out. Normally, 20 is written as (二å, would be vertically written in the postmark). But for calendars, the traditional character used is actually (廿). I believe the top character in the date is actually a very badly smudged/damaged 廿. Hence, I suggest the postmark date is more likely 21Nov1954.

Regarding the "Ng Ping" being at the bottom of the address, I think you misunderstood? It is the 2 characters at the bottom of the postmark (see purple circle) -- that is a transcription based on Cantonese pronunciation. I believe that transcription and its interpretation may be in error. The postmark top and bottom arc segments will always be read in the same direction, although that direction may vary among the different postmark areas and time periods. In your example, the top Guangzhou (also historically transcribed as Canton or Kwangchow) is clearly read from left to right, therefore the bottom arc segment is also read from left to right. Therefore, it would be "Ping Ng", not "Ng Ping".

However, in my opinion, it is still not "Ping Ng". The original incorrect transcription "Ng Ping" might actually make sense as a post office or district name, because it would mean "five peaces", which is actually a pretty name. But I don't think that's what it says. Your friend thought they saw the characters "平五", which makes no sense when read from left to right. I think it says "下五", where the left character is badly smudged. 下 means down (or after, next...), and in the context of time stamp we can assume it is shorthand for ä¸‹åˆ (afternoon). Therefore, the bottom 2 characters (to me) mean 5PM.

Sorry for the long post. Just trying to explain why I think there was an error, and also explain my reasoning.

I'll try to look over the rest of the translation later this week.

Again, very nice article!

k

Login to Like

this post

re: Chinese translation please

Again, thank you! I told my wife that, based on your first post, I had had an epiphany, and it seems I was right. I'll re-work the pertinent portion of the web page.

Bob

Login to Like

this post

re: Chinese translation please

While the name of the road is normally transcribed, I think you did a good job of explaining the meaning of the name of the road. Things like that are very useful, informative, and make for good reading.

Since I am neither a native reader/speaker of Mandarin/Cantonese Chinese, I welcome any comments or corrections to my transcriptions/translations/explanations.

Login to Like

this post

re: Chinese translation please

I can pass along two reliable Chinese/Japanese factoids:

- While Chinese characters appear in Japanese, they often have an unrelated meaning. This is usually taken to mean that the graphicon itself was 'borrowed', eg, found attractive or useful for one reason or another.

- If you are dealing with Chinese military mail - in the broadest sense of that word - it can be useful to remember that the Chinese navy works in Cantonese, while the rest of the Chinese military works in Mandarin. Yes, they use translators at the different command levels & points-of-contact to facilitate inter-service cooperation.

Cheers,

Login to Like

this post

05:17:26am

re: Chinese translation please

Bob and I are talking about unrelated issues under the same topic heading and general intention: Chinese translation. As my question was answered earlier, I have no problem with the discussion continuing in another direction and, in fact, have learned a lot more as the nuances of Chinese and Japanese writing are explained.

I did know that spoken Chinese (and now I know, spoken Japanese) had a lot of variety depending on regions, and even within regions. Where I grew up through my early teens, Hong Kong, we were exposed to mainly Cantonese and its dialects (not sure if that is the correct term for the variations on "typical" Cantonese). Farmers in the New Territories near the border with China, for example, spoke a type of Cantonese that we city dwellers could almost not understand, and those who were from areas closer to Canton itself spoke differently that those who grew up in Hong Kong proper. However, all Chinese who could read, would be able to read the script independent of how they spoke the language. I guess this is like written English, which can be read by Canadians, US Americans, English, Irish, Scots, Australians, etc. despite differences in spoken English between and within these groups.

Login to Like

this post

Silence in the face of adversity is the father of complicity and collusion, the first cousins of conspiracy..

19 Aug 2015

07:39:57am

re: Chinese translation please

" ... it can be useful to remember that the Chinese navy works in Cantonese, while the rest of the Chinese military works in Mandarin. Yes, they use translators at the different command levels & points-of-contact to facilitate inter-service cooperation. ..."

Amazing detail. Does the CIA know this ?

What a potential source of confusion.

1 Member

likes this post.

Login to Like.